‘Woke Advertising’ and The Double-Edged Sword of Piggyback Marketing

The trials and tribulations of trend-based content In 1999, Scott Goodson founded StrawberryFrog, an agency dedicated to ‘movement marketing’, a strategy model that begins with an idea on the rise in culture. Defined by its method of using marketing to understand not to persuade, ‘movement marketing’ has revolutionised the way brands interact with consumers. In […]

The trials and tribulations of trend-based content

In 1999, Scott Goodson founded StrawberryFrog, an agency dedicated to ‘movement marketing’, a strategy model that begins with an idea on the rise in culture. Defined by its method of using marketing to understand not to persuade, ‘movement marketing’ has revolutionised the way brands interact with consumers.

In more recent years, businesses and marketers on the largest of scales have undergone something of an ethical awakening, or are at least attempting to appear like they have. The boundless platforms on which companies are able to project from, are suddenly being engineered as a force for good and the ‘sell’, as we once knew it, is about values, not the product. Consumer investment has become far more symbolic, with divisive content sending out a message that obstructs people from sitting on the fence. In an increasingly saturated market of politically engaged content, efforts to repurpose material can, however, appear opportunistic or bogus.

Adland was once an alternate reality, where we could look ‘better’ and immerse ourselves in a supposedly idyllic world. For better or worse, the landscape of marketing in 2019 is different, forcing companies and consumers to have conversations that we’ve been reluctant to have. However, in a world where public image and opinion hangs by a thread, the decision to use issues and debates in your marketing strategy simply cannot be for everyone. The fundamental dangers to content in this space are its authenticity, its sensitivity and, finally, timing. I want to explore the upshoots of effective piggyback marketing and its intricacies that make it such a risky endeavour.

Sense and Sensitivity

An unsurprising majority of content does not bear a deeper meaning and can gain coverage through conventional interest from anyone. When subject matter drifts towards the slightly more contentious, content must then opt to be subtle or confrontational in its delivery.

Whether you’re first in line or simply latching onto a discussion on any topic, the pace at which social media moves and reacts means that the stakes have never been higher. Agencies and brands can use issues and events as a basis for their content, which can then be hijacked by others, but it is often the tact in which marketers approach these topics through which they are judged.

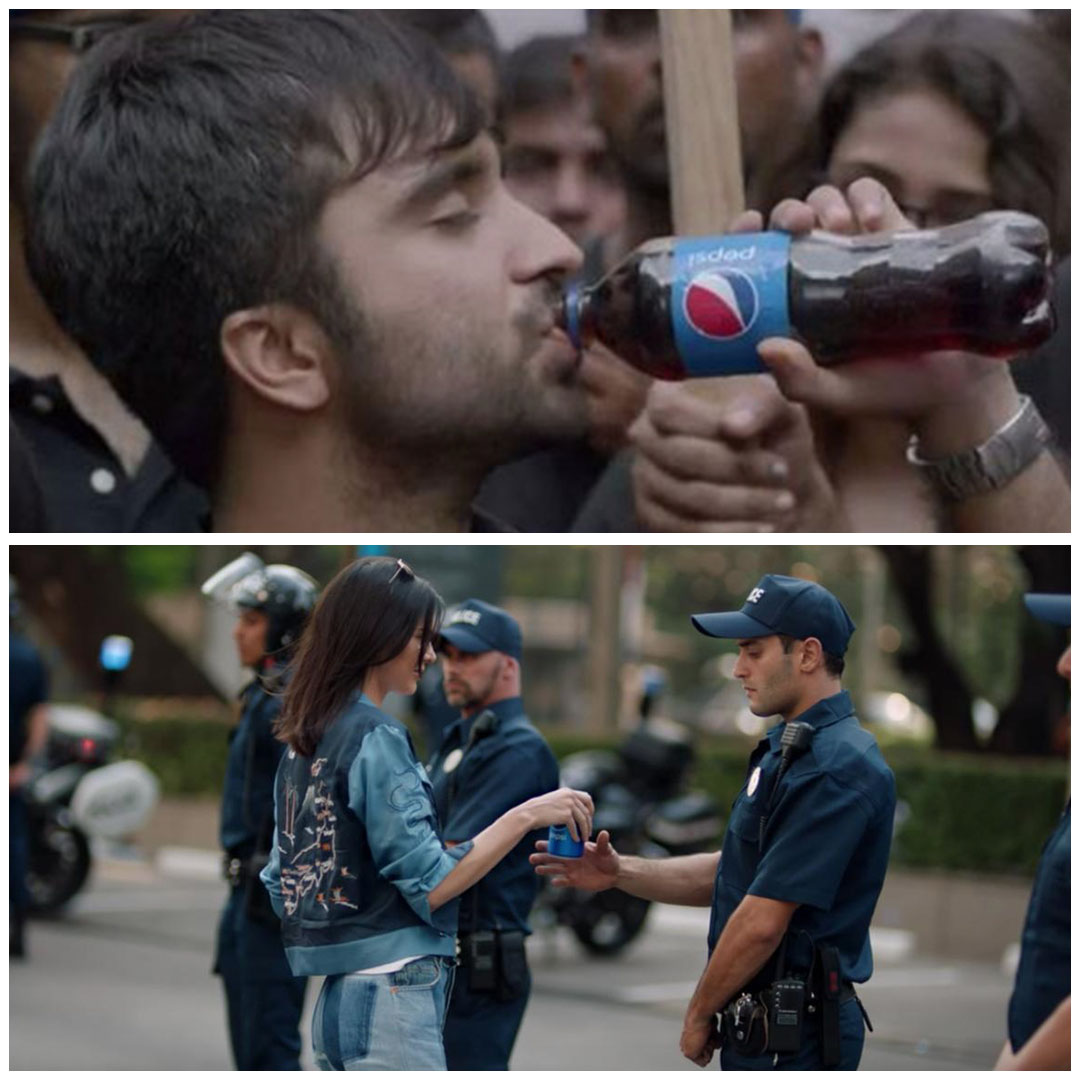

In 2017, soft drink manufacturer Pepsi infamously decided to make light of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, pacifying the pursuit for social injustice to a jovial scene where model Kendall Jenner offers a police officer a drink. The almost instant furore (exemplified by the online reaction of Martin Luther King’s daughter, Bernice) was subsequently followed by the removal of the ad and a swift apology from the company.

However, this indefensible error of judgement was sadly not the first time Pepsi had ventured into more politicised imagery through their content. A 2015 video released by Pepsi in India appeared to mimic the protests of Pune students who partook in a hunger strike, showing an acting protestor succumbing to the seemingly irresistible drink stating ‘Pepsi thi yaar, pi gaya’ (It was Pepsi, so I had to drink it). Similar to the video that Pepsi released just under 2 years after, the ad trivialises the activist efforts of students in India in what was a prime example of a company looking to ‘cash in’ on a topic of interest.

While creating material off the back of another brands success is a way of playing it ‘safe’, arriving first to the party leaves you in a minefield of criticism. However, Pepsi have proven in rather dramatic terms that lightning does strike twice, and a revamp of a controversial campaign is as unpopular on the second attempt. What added fuel to the fire for their second ‘protest’ ad, was how it incorporated the often-criticised technique of using an influencer to further promote their already disingenuous message. For many, the apologies that follow these campaigns fall flat for the fact that even armed with hindsight, these campaigns are seen by enough eyes to see the red flags.

Regardless of the uncertainty of ‘movement marketing’ in terms of emotional response, examples of positive engagement with important topics are rife. Last year, a far more abstract approach to a more conscious form of marketing came in the form of an online game from Indian NGO Project Nahi Kali. The organisation, which supports education for underprivileged girls, used an innovative concept to spark debate called #PowerlessQueen where users played a game of chess against an automated opponent but without the use of the queen piece. This game can be seen as a figurative exploration of the life of Indian women and their basic rights to facilities such as education. The NGO teamed up with WATConsult digital marketing agency for what proved to be a subtle but hugely effective example of meaningful content, winning a Grand Prix at the Prague International Advertising Festival.

What sets this example aside from the two efforts from Pepsi is not simply that Project Nahi Kali is a more transparent organisation void of the ‘agenda’ we assume from hugely affluent commercial corporations. As well as being literally user-operated, the game allows those engaging with the content to think for themselves, presenting a much more figurative message that isn’t expedient. The content is open-ended in the same way that using objectivity over emotion can yield a higher response. Last year, we took an in-depth look at the deeply saturated topic of gender in relation to the usage of Cryptocurrency for online financial trading platform, eToro. Simultaneous discussion on both topics is scarce, and for our infographic, which gained huge results, we wanted to focus on the data without the blatancy of some material that we so often see circulate. Visual material in this arena is best when it starts a conversation, not when it attempts to have the final say in an almost grandiose manner.

Authoring the Authentic

A much discussed component of any marketing strategy is how genuine a brand’s voice is. Engineering your content in a way that is true to its values is not a new concept, and nor is it specific to ‘movement marketing’. Sadly, while the involvement of such a large number of global corporations in socio-political issues is positive, it can in some instances appear like a desperate attempt to capitalise and stay relevant.

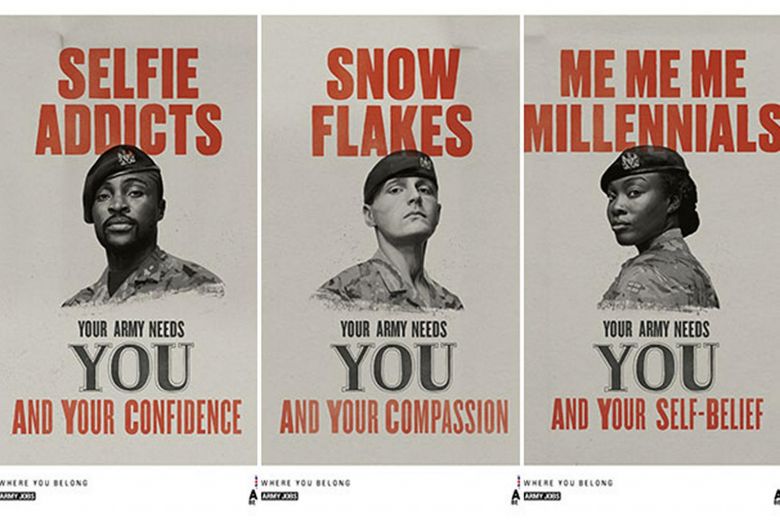

A prime example of a brand manipulating popular issues and language for their own gain came at the start of 2019 with the British Army. Their newest recruitment campaign combined Lord Kitchener’s ‘Your Army Needs You’ message from WWI with the popularised stereotypes of ‘snowflakes’ and ‘millennials’. The ad is designed to show how negative perceptions of young people are assets to an army, but while largely satirical, it has since been met with criticism on social media. Younger generations have become increasingly disillusioned with our armed forces in recent years, with this ad being an attempt to subvert modern stereotypes.

Unfortunately, the reaction amongst some was that the campaign was a misdirected attempt to engage with certain demographics, and using already popular tropes in order to do so. However, in what is a large spectrum of campaign failures, this can be seen more as a representative case of using modern phrases in a slightly contrived manner rather than anything severe. In a former post, I discuss the importance of emotional awareness in the creation of viral content and how a brand lacking honest sentiment can result in less engagement. The takeaway from a campaign such as the British Army’s, is that if the choice arises between using ‘fashionable’ terms and topics for the sake of it, or not at all, then stick with the latter.

This month, FMCG Procter and Gamble ignited a media frenzy with Gillette’s ‘We Believe’ campaign that attempted to tackle toxic masculinity, bullying and sexual harassment in what will definitely go down as one of this years most discussed ads. Sid Lee executive creative director Reid Driscoll claimed the ad was a ‘fresh approach’ to the topic that ‘shows all of us, as men, how we’ve hurt and been hurtful in the past and how we can stop it now and for the future’, emphasising how the ad does more, in a short clip, than companies have done for gender and masculinity for decades.

For many people, and for many reasons, the advert was hugely controversial coming from a company that has stated their product to be ‘the best a man can get’ for years, showcasing sportsmen and celebrities as idyllic projections of what a male should look like. However, it is their existence in this world that makes their standpoint so effective demonstrating the cathartic learnings of a company with previously damaging inherent values which can trickle down to its consumers. While divisive, Meltwater gauged the immediate reaction to be positive, with 59.5% positive sentiments across different channels compared to the 16.3% that were negative. It is the self-critical nature of the advert that makes it authentic which requires a level of emotional intelligence that often dilutes as the scale of a company increases. It’s undoubtedly naive to wholeheartedly commend content from a personal care brand, but amongst the multitude of tone-deaf material we so often see, it provided a welcome break and, for many, a sign of progress.

To conclude, as the world of content becomes even more saturated, it becomes easier with every passing year for consumers to see through the forced efforts of marketers. This slight power shift prevents brands from telling consumers what to think, whilst simultaneously leaving themselves exposed to mass criticism in their adverts to promote a message or movement. Social media is an arena controlled by the masses, where the progressive are adulated, and the opportunists scorned.

Search

Search PR

PR AI

AI Social

Social