Anger and Engagement – The Currency of the Attention Economy

How playing with fire can make or break your campaign On the 10th of March, 1977, the Sex Pistols staged their signing to A & M records a few hundred feet before the gates of Buckingham Palace. Their already palpable notoriety had reached a form of zenith, with the pure indignation they provoked only lifting […]

How playing with fire can make or break your campaign

On the 10th of March, 1977, the Sex Pistols staged their signing to A & M records a few hundred feet before the gates of Buckingham Palace. Their already palpable notoriety had reached a form of zenith, with the pure indignation they provoked only lifting their profile further, showing undoubtedly that, in that moment, there was ‘no such thing as bad publicity’.

The man who engineered this landmark moment of public enragement was Malcolm McLaren, who knew that photos and press junkets from the actual signing of the contract in some offices the day prior was unlikely to raise any eyebrows or sell any records. Depending on who you talk to, punk was dead within about a year, and everyone had to get proper jobs, even Johnny Rotten who briefly marketed butter to the nation.

Forty years on, punk is now a distant memory for some, but Malcolm McLaren’s marketing legacy of upsetting apple-carts and rattling cages lives on in many forms. Publicity in the modern age, like punk was, is instantaneous but also boasts the danger of being short-lived. The sheer immediacy of the world we now live in makes it all to easy for any material released by a brand, group or living entity to get onto every news feed imaginable.

For many, marketing is simply a quest for prominence and acclaim, often fuelled by the primitive emotions of an audience. But while the sentiments we look to excite are basic, there is a complexity in allowing the human element of your brand into the public domain that forces many to remain on-the-fence. Like the late Malcolm McLaren, I want to explore how emotions can create a strategy, but specifically how anger is engineered as a means of garnering attention and engagement. From masterstrokes to misdemeanours, what learnings can we take from the emotional marketing ‘hall-of-fame’.

The Heist

In a time where the legitimacy of news content is under constant scrutiny, marketing stunts or hoaxes for the benefit of brand awareness are now often confined to April 1st. Many brands are positioned in an industry where these ploys would be deemed inappropriate or simply an attempt to curry favour with a wider demographic. For the companies that can, and indeed do, stick their heads above the parapet, contentious campaigns of this nature can give your brand personality, but inevitably ruffle a few feathers along the way.

Recently, one of the trailblazers in this realm of marketing has been Paddy Power, who have been able to utilise controversy as an effective tool. Over many years, the Irish bookmakers have offered up some of the most inflammatory yet ingenious marketing campaigns, changing the way competitors and consumers view brands of this nature.

Their most recent stunt, many have argued, is their finest triumph which had the entire footballing world, for a brief moment, hoodwinked. Last month, Huddersfield Town announced their official partnership with Paddy Power which would run throughout the following season, and also result in a new kit featuring the brand logo.

As shown above, even beyond the low standards we often expect from a bookmakers emblazoning their logo on a team strip, this was by far one of the worst the world had ever seen. The now-infamous sash-kit instantly went viral, with every major national publication, the Football Association and thousands of Twitter profiles expressing their dismay at such a catastrophic decision by the Yorkshire side. The ruse continued into the evening, where Huddersfield even played in the infamous shirt, before it was revealed the following morning that it was, of course a hoax.

Paddy Power were still sponsoring Huddersfield, but removing all branding as part of their SaveOurShirt campaign to encourage companies to remove their names from the team shirts worn by players and supporters. Furthermore, the success of the campaign has now led to 3 more British sides agreeing to the donning of non-branded shirts for the coming season. For Paddy Power, the obvious approach would have been to announce the non-branded shirts, and the accompanying hashtag, disregarding the stunt as a whole. However, when approaching an issue or topic already shrouded in anger and avid discussion, Paddy Power were able to harness that emotion through the media storm they created and, eventually, flip the entire thing on its head.

A critical element of their success was how they controlled the narrative of the campaign, allowing the pandemonium to unfold just enough, before they revealed their trickery to the duped national press. Playing up to the ardent passions of sports fans can be a dangerous game, but can be fool-proofed by an amalgamation of sensitivity and impartiality. For instance, for our client Crusader Vans, we produced a campaign aimed at triggering the debate between the most committed football fans but focussing solely on who clocks up the miles travelling to away fixtures. Our goal was to exploit the heightened state of competition among fans, but swap in data for bias to allow those engaging with the content to make their own arguments.

The Faux-Pas

A common thread among the many failed attempts at emotional marketing stems from the previously-discussed trope of losing control of your narrative. Regardless of the excessive time spent planning and structuring the message you want your content to have, the power you have recedes from the second it is given to the world. As mentioned, the pace at which the world of social media and news operates means that a campaign can go live, and by the time you’ve finished your lunch your brand is cancelled, the police are outside and there’s a baby crying.

Beyond the retracted statements, extended apologies and open-letters that follow a PR blunder is the common thread of lacking foresight when entering the realm of emotionally charged topics. While positive results are boundless, falling foul of insensitivity or inauthenticity is a more prominent risk when producing content that triggers conversation or reaction.

A prime instance where a brand has been good in their intentions but severely missed the mark was Brewdog’s ‘beer for girls’ campaign from last year. Their repackaged punk IPA, sold at a cheaper price for those who identify as female, was done ostensibly to demonstrate their own opposition to the gender pay-gap.

The independent brewer also pledged to donate 20% of sales to causes that battle inequality among genders, but the positive message was not reciprocated with a positive reaction from individuals and groups across social media. Many criticised a tongue-in-cheek approach to a serious societal concern, while some found the move as a disingenuous attempt to gain a share of the female drinkers market. Following on from the equally controversial ‘No Label’ beer aimed at being the world’s first ‘non-binary, transgender beer’, many simply accused Brewdog of using piggybacking methods to gain publicity, and satirising important issues for their own financial gain.

The accusations, articles and statements highlight, plainly, the dangers of losing a grip on the narrative of a campaign, particularly when you don’t have a ‘plan b’. Brewdog, in their attempt to stem the angered responses, stated that the campaign was ‘an overt parody on the failed, tone-deaf campaigns that some brands have attempted in order to attract women’, which simply re-explained the joke that everyone understood, but did not find funny.

An observation we can take from a comparison of Brewdog and Paddy Power’s approach to emotional marketing is the difference in how sincerity is conveyed, and the feelings they were trying to evoke. Brewdog were also left open to criticism in that they were entering a realm of discussion that they themselves were involved in, with many asking for the company to divulge on their own approach to female recruitment. Whilst an overt awareness of key issues facing society is commendable, any disregard to the ‘people in glass houses’ mentality can often backfire.

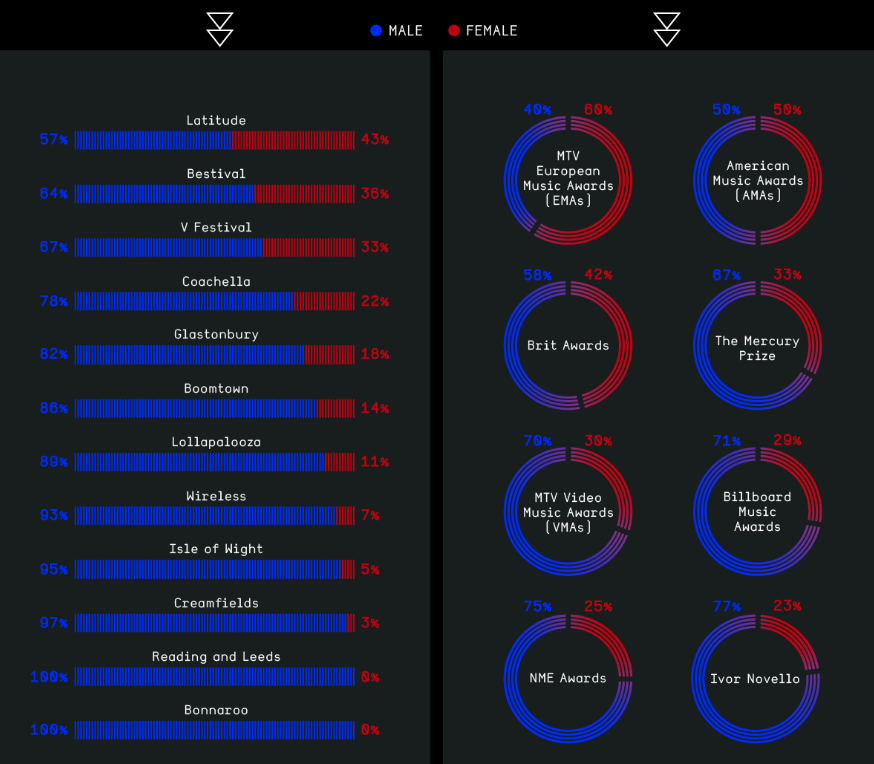

At Kaizen, we use data to create a more objective approach to the content we produce, as well as a grounded understanding of the position our clients operate within. Last year, we released a study of the gender gap in music awards and festivals for streaming service, Last.fm, in an infographic that presented facts over opinion. The avoidance of finger-pointing meant that the piece acted as a platform from which a discussion could be formed. This approach has acted as a guideline throughout our history of producing content, and has provided us with a framework through which we can operate within contentious topics in a more pragmatic manner.

Final thoughts

To conclude, for as long as the comment sections, Twitter threads and reaction pieces exist in our digital society, the need for emotive content will persist. If you’re building a brand story, or creating a tone of voice, it’s often important to take the plunge into this world, but this can and should only be done with caution. Whilst signing a record deal outside of Buckingham Palace isn’t going to be for everyone, there will always be an effective way to use (but not abuse) emotion in your strategy.

Search

Search PR

PR AI

AI Social

Social